California producer eliminates the need for settling ponds and captures water for reuse.

Any time an aggregates producer can provide sound environmental practices while improving its own profitability, it is on the winning side of the production equation. Sustainability in the aggregates industry is a business approach that has gained considerable attention in the past several years. The BoDean Co., Inc., of Santa Rosa, Calif., however, has applied a sustainable approach to its business practices almost from day one.

Any time an aggregates producer can provide sound environmental practices while improving its own profitability, it is on the winning side of the production equation. Sustainability in the aggregates industry is a business approach that has gained considerable attention in the past several years. The BoDean Co., Inc., of Santa Rosa, Calif., however, has applied a sustainable approach to its business practices almost from day one.

Dean and Belinda (Bo) Soiland opened BoDean Co. in 1989 with the purchase of the Mark West Quarry in the northern Napa Valley. The quarry has been in operation since 1910, and the Soilands put plans in place not only to reclaim mined-out land, but also to begin using a benching method as they continued to mine. Over the past 20 years, this system of benches has improved safety and operational costs, remediated stormwater runoff, and helped to better manage the mine plan in general. BoDean Co. has since applied the same practice to its newer Blue Rock Quarry in Forestville, Calif.

Both the Mark West Quarry and the Blue Rock Quarry supply aggregate material for customers in the surrounding area, as well as to BoDean Co.’s vertical asphalt operation in Santa Rosa. In 2006, in order to combat the cost of purchasing sand for its asphalt plant, BoDean installed a washing plant at the Mark West Quarry and began to produce its own sand. The wash plant includes a blademill, washing screen, cyclone, and dewatering screen. At the same time, BoDean opted to install a Phoenix HiFlo circular thickening plant and an overhead beam Diemme GHT 1500 P13 recessed-plate-frame filter press at the end of the washing stage to capture and reclaim as much water as possible.

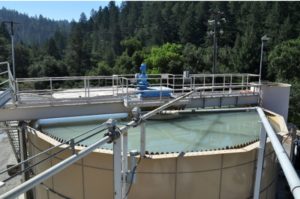

According to Robb Folmar, site manager for the Mark West Quarry, “We don’t have space for settling ponds, and water is hard to come by here with just a pond above the plant and a creek below.” In addition, the footprint shared by the processing plant and loadout area within the quarry is very tight. Because of this, he says, the wash plant operates in a closed circuit with fresh water coming off the thickener over a weir through gravity overflow to a fresh water tank, pumping back to the wash circuit. The underflow thickens from about 4-percent solids by weight to about 50-percent solids. This mud slurry feeds the filter press, which removes the remainder of the water and produces hard cakes of filtered fines that are up to 90-percent dry.

The use of belt presses to claim moisture from fines is not unusual in North American aggregate operations. The application of plate presses for aggregates dewatering, however, is new in the United States. BoDean Co.’s plate press, manufactured by Diemme S.p.A. of Italy (now represented in the United States by Louisville, Ky.-based Phoenix Process Equipment Co.), operates by compacting mud slurry between 140 vertical plates that are each about 5-foot square, until the end product is a dry cake that drops beneath the press for loadout.

“Dean had seen Diemme presses used in mining in Europe, and he thought the method would work well for us,” says Folmar. “He is really good at looking forward to the bigger picture and applying his ideas to the company.”

The washing and dewatering plants were installed and running by mid 2006. Folmar explains that fines-laden water slurry captured from the wash plant is pumped to the circular thickener. A dry polymer make-down system mixes dry batch polymer flocculants with water and injects the polymer into the slurry upstream of the thickener. The flocculants attach and help the fines to settle more quickly to the bottom of the tank. The clarified water at the top of the thickener tank flows over weirs and uses gravity to run into the fresh-water tank, where it is pumped back to the wash plant for reuse. BoDean Co. owner Dean Soiland explains that, while a system of totes can be installed to premix the flocculants, he prefers having his crew mix each 250-gallon batch individually for better control. This is because plate presses typically require significantly reduced polymer usage.

From the bottom of the thickener, the slurry of 50-percent solids pumps to holding tanks adjacent to the filter press. A nuclear densometer calculates mud density as it enters the press.

“The press works over pressure and time,” says Ian Scroggins, wash plant operator for the thickening/filter press system at the Mark West Quarry. Scroggins explains that each press plate is covered by its own filtering cloth. The plates hang vertically in a row. At the beginning of a cycle, pumps fill the spaces between the plates (called chambers) with the thickened slurry mixture. The plates work like a mold as they slowly tighten to 225 pounds per square inch, compacting the fines between them and filtering the water first through the outer layer of mud, through the cloths, and finally through holes in the plates to be captured beneath, where it is sent back to the fresh-water system.

At the end of the cycle, when the maximum amount of water has been pressed from the fines, the press opens at one end and the plates move aside one by one at a speed of 30 plates per minute, allowing the caked fines to drop to a stockpile below. The filter cakes weigh 300 pounds each, for a total of 21 tons processed per cycle.

“We pump a slurry that’s 45- to 50-percent mud. If we pumped more often, we would have more water in the slurry and a wetter cake at the end of the process,” Scroggins says. “We can make the cakes as dense as we want.” The caked fines that drop from the filter press are so dry and compact they have a consistency of hard clay. “For the reclamation of water, you will never get anything as dry as these cakes from a (traditional) belt press,” Scroggins adds.

Scroggins says that a full press cycle takes about an hour. Because the thickener makes more mud than Mark West Quarry can process through the filter press in one shift, the press is programmed to run automatically after personnel leave the quarry at the end of the day.

“The press could run 24 hours a day if we wanted,” he says, “but, typically, we set up the thickener to fill the mud tanks to capacity before we leave for the day.” The filter press processes it automatically, running 16 to 18 hours per day and shutting off when the tanks hit a certain level. In the morning, when a shift begins, the fines are all in cakes at the bottom of the press, and there is no mud left in the tanks.

Within two months of the press’ startup, BoDean built a second mud tank to hold more fines slurry for processing through the filter press, according to Folmar. “The initial cost to purchase this press was more than if we had bought a belt press,” he says. “But over time, if you don’t have storage for additional drying of fines or room for settling ponds, it pays for itself. In fact, with this technology, settling ponds may just go the way of the past.” Additionally, BoDean Co. has found a local use for the filter cakes that carries its sustainable practices even further — selling the material for use as pond liners in Napa Valley’s wineries.

Folmar says that because BoDean was the first aggregate operation to install a plate filter press in the United States, and the manufacturer wasn’t represented in the U.S. aggregate market when the press was purchased, making the learning curve tougher for the operation than it might be today. Having a domestic distributor has been helpful, he says.

Scroggins agrees, noting that it bridges a gap with parts availability. “We can’t have downtime with the press because that bottlenecks everything. If the machine went down, and we had to wait for parts to ship from Italy, we could be completely down for more than a week,” he says. “So it’s nice to have a U.S. distributor in the industry.” Phoenix has also been working with BoDean to test cloths for the plates on the press, working to find an optimal weave to tweak the system and further raise efficiency.

In keeping with its spirit of self-reliance, BoDean handles its own drilling and blasting, shooting once or twice a week as needed to meet demand. At the end of the mining cycle, BoDean also handles reclamation internally, planting native grasses and vegetation, and moving trees, including redwoods, on site to preserve them as the mine expands.

The Mark West Quarry employs a primary jaw, a secondary cone, a tertiary vertical shaft impact (VSI) crusher, and a tertiary screen that recirculates materials to the secondary crushers as needed. From the secondary stage, a surge tunnel feeds the wash plant, which consists of a scalping screen, blade mill, triple-deck wet screen, and a cyclone and dewatering screen. The quarry produces material from 1-inch down to sand; washed material includes 1-inch by #4 and 3/8-inch. The wash plant also has a VSI crusher as part of the circuit. This allows the company to make all sand material, if necessary, by running coarse material back through the wash plant and reducing it through the VSI.

“We’ve seen a lot of wash plants with water just sitting around the equipment,” says Soiland. “We want to drain and recapture as much water as possible, so the wash plant is sitting on asphalt. Even water that’s dripping off the plant is caught in basins and sent back for reuse.”

“This operation ultimately hinges on the press. Without this press, we wouldn’t be able to have the wash plant,” Folmar says. “When we had to purchase sand for the asphalt plant, it was really expensive. By manufacturing our own sand, the wet plant has slowly, but surely, paid for itself.” AM

by Tina Barbaccia –aggman.com